Begin at the main entrance, with the university colleges behind you. If you pause for a moment to listen, you should hear the traffic and trams in nearby streets, maybe distant yells from the two sports ovals you are sandwiched between. Were you ever good at sport in high school, or were you the one to hang back, like me, too awkward in their body to fully commit to playing competitive sports with a bunch of sweaty, hormonal teenagers who didn’t really know you? I think I would have liked to participate in: cricket, softball, netball, le cross. Not the ones where you are tackled—my body is soft and I don’t care to be knocked to the ground.

But anyway—walk forward and enter the cemetery. One of the first things you will see, to your right, is the Prime Minister’s Memorial Garden. Indulge me for a minute and walk inside, entering through the beautiful green pavilion with double doors and lots of windows. Once you have passed the second set of doors, you will be facing a small pool with monuments and trees on either side of the garden. Here is where old leaders of the nation come to die—well, to be buried. Even then, it is only the prime ministers who were born in Victoria. Robert Menzies. Malcolm Fraser. James Scullin. You see that triangular prism, on the north side? That is the memorial for Harold Holt, the 17th prime minister of Australia who disappeared one summer’s morning off Cheviot Beach. You know the guy—they named a swimming pool after him, there are conspiracies that he faked his death or was taken by a Soviet submarine, and he was a big fan of hot women (I mean, same). Walk closer to his pyramid memorial and read the gravestone: he loved the sea. Well, isn’t it fitting then that the sea carried him home, “like a leaf being taken out” said Marjorie Gillespie, who was with him at the beach when he disappeared. That cursed beach, already named after the wreck of SS Cheviot in 1887.

Speaking of 1887. Somebody was born that year who I am keenly interested in, and she is buried in this cemetery somewhere. You will have to turn around and exit the PM’s garden, as she doesn’t rest here. She did, however, edit a journal with Robert Menzies while they were students at the University of Melbourne, and later argued against him at a public debate on conscription.

Once you have left the memorial garden, turn right and walk up the entrance avenue until you reach your first fork in the road. There should be a mausoleum in front of you, and an Elvis Presley memorial close by. Much like Harold Holt, Elvis is not actually buried in this cemetery. But we do know where Elvis is, at least—unless Elvis is the one lost at sea, and Harold lies at Graceland.

Turning left and walking north will take you along curved paths through the Roman Catholic and Methodists divisions. Turning right to head south will lead you through those buried in the Church of England section, along with a small area reserved for Chinese people and, in the far southeast corner, a Jewish section. But we are heading straight ahead, to the east side of the cemetery, where Katie Lush lies with her family in the Baptist division.

I came here once with a girl I had a crush on, the girl who was my first kiss, and we wandered through Church of England graves commenting on names of the dead as we tried to find Katie. We were lost even though I had looked up where Katie’s grave was the night before, on a website called findagrave.com. Maybe I was dawdling on purpose, hoping to stretch out the time with my friend and crush for as long as possible. This would be the last time we’d hang out, but I wasn’t aware of it at the time. All I was focused on was keeping warm on an early winter’s afternoon and maintaining her interest with this strange game of treasure hunt. Eventually, we turned and headed towards the Baptists.

There are 300,000 burials in this cemetery, stretching across 43 hectares. It has been collecting bodies since 1853. I have been thinking about death a lot in the past month, due to reading a book about dissection, and due to an old friend dying suddenly. Not old in the sense of age—she was only twenty-six—but old in the sense I hadn’t seen or spoken to her for a couple of years. It’s the normal process of life, I suppose. You work or study alongside someone for a few years, then one or both of you leave the job, school, or town, and unless you were the closest of friends, conversation eventually dies.

When I heard of her death my brain unlocked all the memories I had of her, carefully filed away in folders titled Woolworths: 2012, Woolworths: 2013, right up until 2021. We worked together for almost ten years and she made me—and everyone—laugh until there were tears in my eyes. She was tall and gorgeous and once made me turn away while she took a selfie, too embarrassed to let me watch as she pouted her lips for the camera. Another time she drove me and another friend to a late-night donut shop in Springvale for my birthday. It’s a cliché to say someone who is now dead was full of life, but she truly was filled to the brim—radiant and glowing.

Where are we now? Stop for a second to catch your breath (or let me catch mine) and take in your surroundings. We need to head to the end of Central Avenue, and then turn left up Tenth Avenue until we find ourselves between the Presbyterian and Baptist graves. If you are lost, look for the signs. You can even pause the audio if you like, until you’re ready to start moving again—I’ll wait for you.

If you are facing the north, then to your right will be a long line of Baptists, where Katie is buried with her family. Step through the graves and see if you can find their large headstone—her grave is number 168.

Katie Lush was born in May 1887. She taught philosophy at Ormond College and was a staunch socialist, campaigning against conscription during the first world war and speaking at public rallies in inner suburbs like Richmond. At the University of Melbourne she met Lesbia Keogh, a young woman from Brighton who wrote poems and had a faint blueish complexion due a congenital heart condition. Lesbia looked up to Katie, attended meetings with her and, after some time, developed a crush on her. In the mid-1910s, Lesbia wrote poems for and inspired by Katie, committing her affection in ink.

I first came to this cemetery in 2019, in early August searching Katie’s final resting place. The day before, I wrote a prose poem in my notebook that went something like this:

How long has it been since someone wrote a poem about and inspired by you? Perhaps a hundred years or more, maybe less, though I’m afraid you may have been forgotten in the wreckage of time, when once you were seen as an Amazon among women. Tall, remarkably tall, and angular—gaunt, some would say, in your later years, though that is such an ugly term. Would you prefer ‘slender’, or is the description of your mortal form insignificant to you, Katie?

I have a few questions, if I may be so bold to ask. Were you insecure in your body, awkward amongst the small women beside you? Specifically, how did the presence of that small, delicate but bravehearted poet make you feel in your body? Did Lesbia’s love frighten you? Were you disappointed, like her, that you did not live in Sappho’s Greece where women were free to kiss each other’s soft lips? Katie, were you indeed lonely, or have you just been represented that way in Lesbia’s shadow? (Are these questions too personal for the dead?)

Tomorrow I will visit you, scatter petals over your grave and bow my head in gentle reflection—how long has it been since warm bodies have touched the soil above you? Maybe not as long as I think. I’ll visit tomorrow but I feel I needn’t bother, in a way, because I’ve encountered your presence before. At the university, the public library, on and electric tram to Kew; you haunt Melbourne softly, impressions of your past lingering.

But I wish I could have known you, listen to your anti-conscription talks and sit in your philosophy tutorial, speak to you and have the pleasure of knowing your secrets. I believe you would have been a woman worth knowing, I believe you are a woman worth knowing still.

Katie is buried with her parents, brother, and her father’s first wife. They have a large monument to mark their resting place, with a prominent cross on the top. The engravings are still perfectly clear, unlike some of the cheaper headstones that have crumbled and faded through time. It gives the impression that this was a family worth remembering—or at least, this was a family with money.

After she died, Katie’s half-sister Mary wrote a letter to their nephew, George. “Soon we are passed and forgotten,” she wrote. “Remember her, George, for a little.” How many of the people around you, under the earth, have been forgotten? On your way out, you might like to read some of the names and wonder what sort of life these people lived. I’d love to join you but I’m late for my train, so I’ll leave you here—don’t forget to blow Katie a kiss for me.

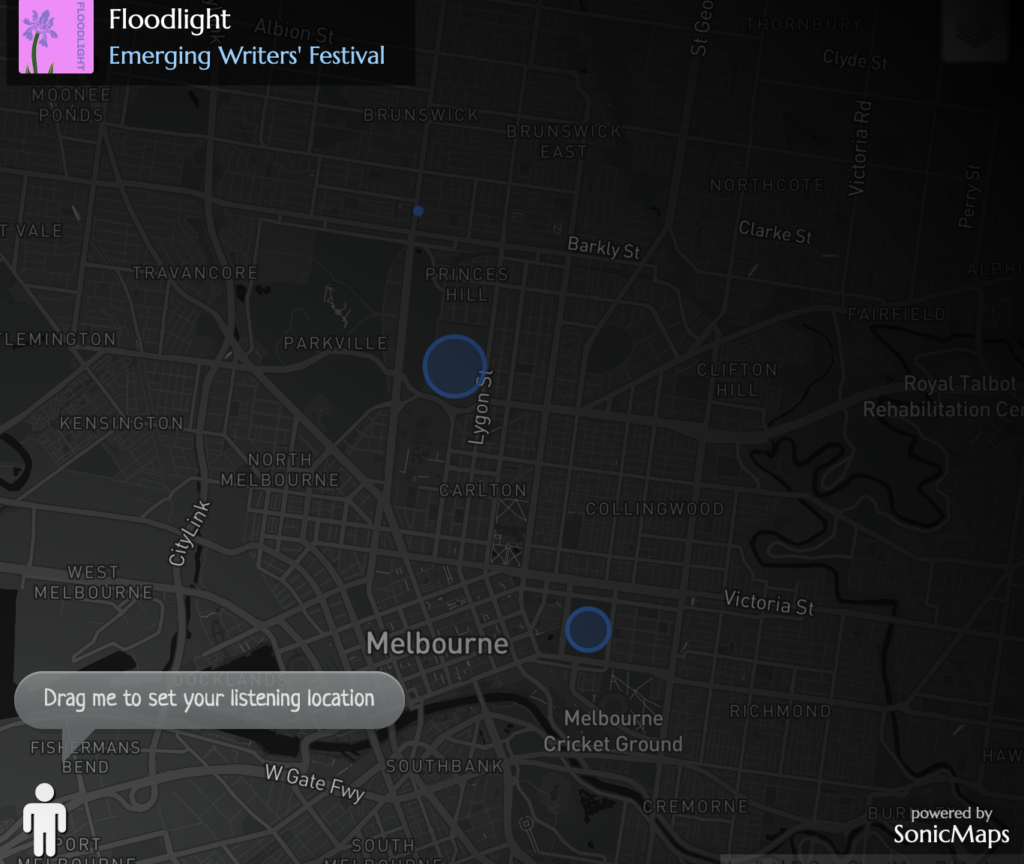

Listen to and explore this digital piece, as part of Floodlights, on Emerging Writers’ Festival’s website here.