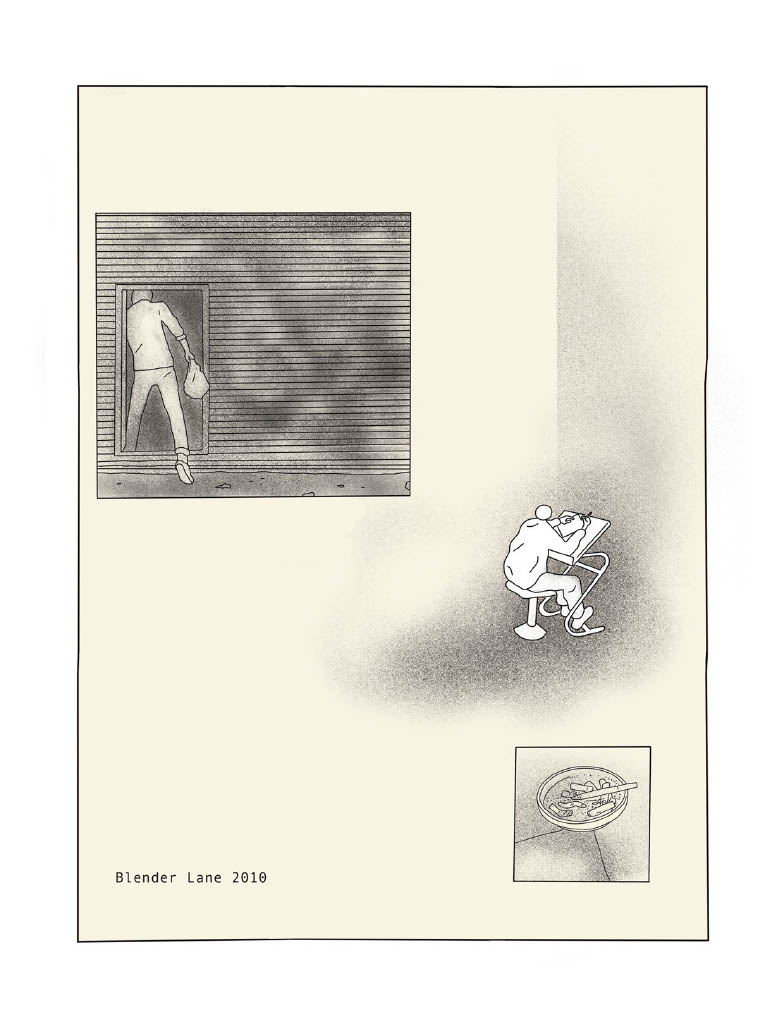

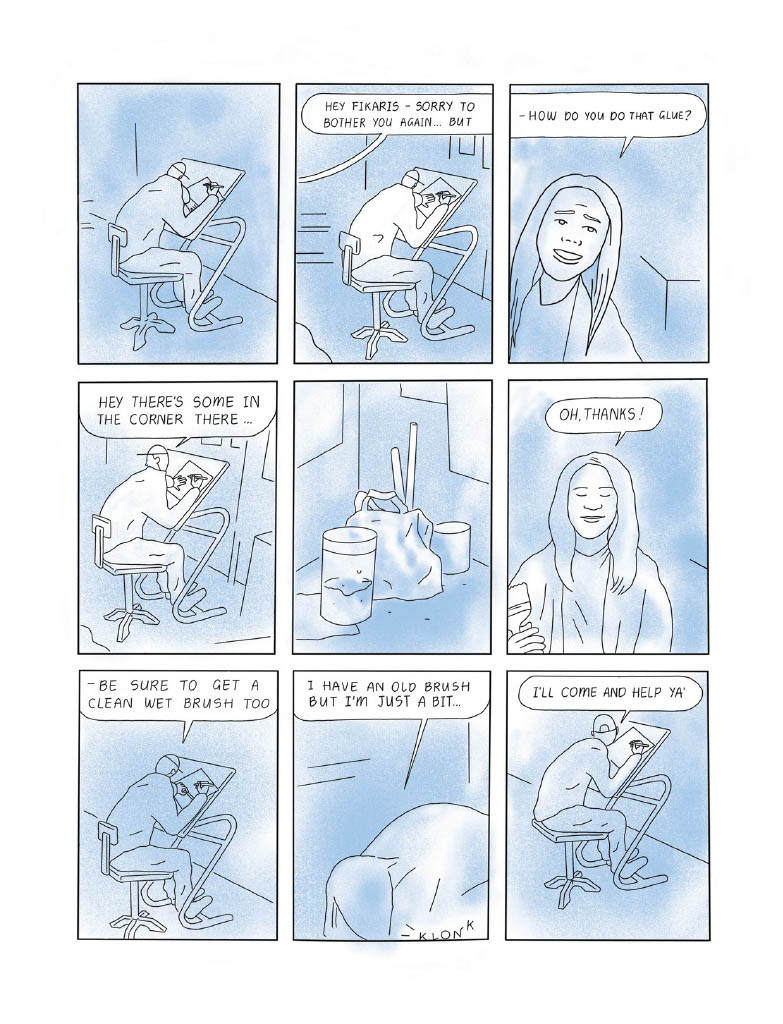

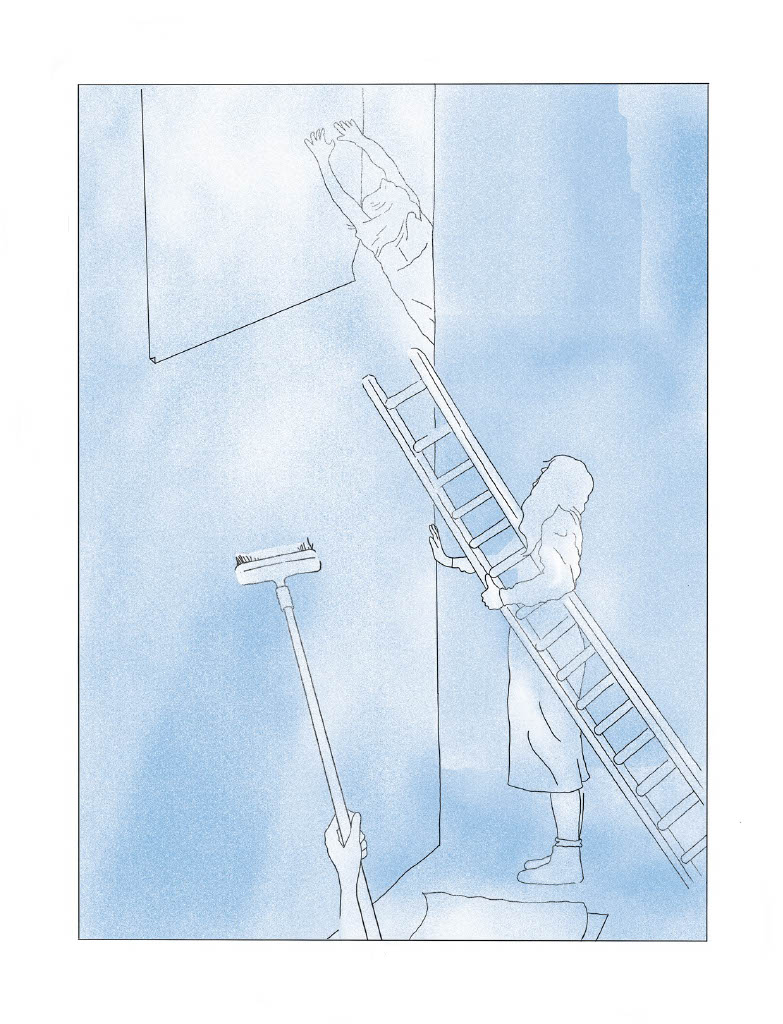

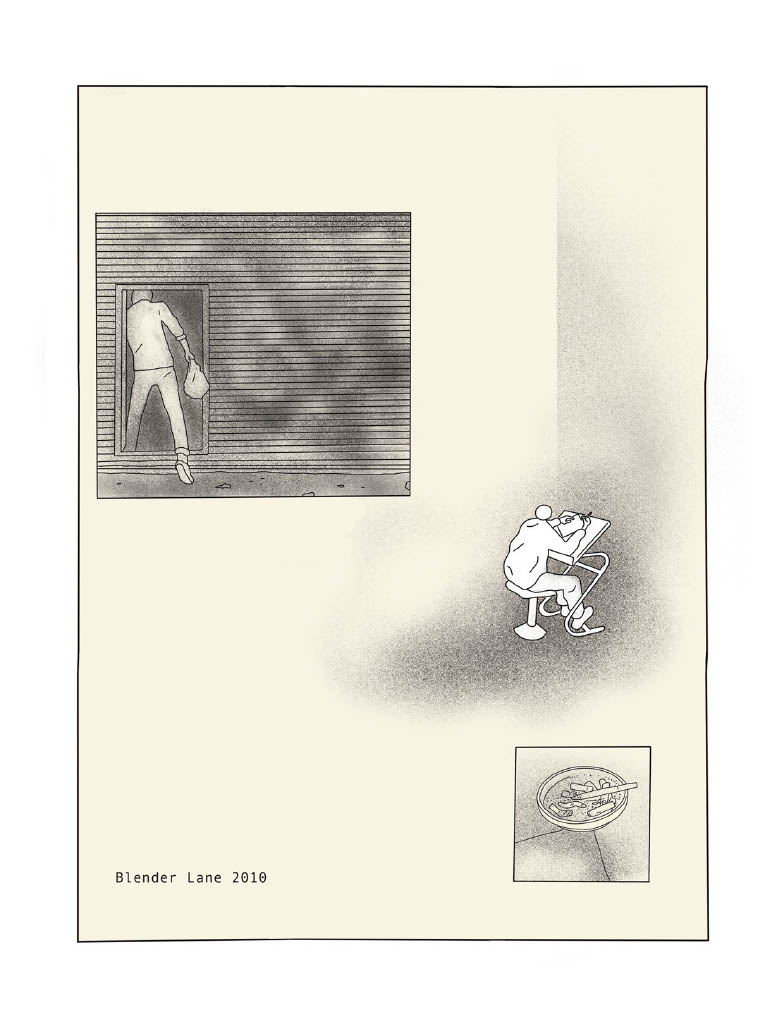

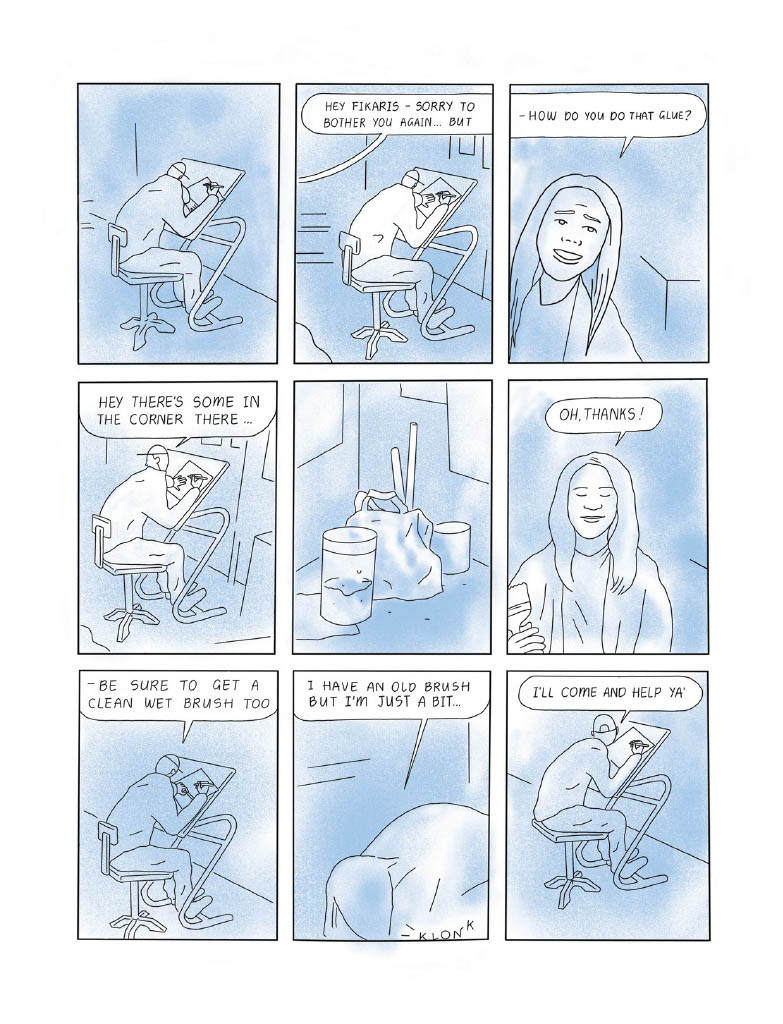

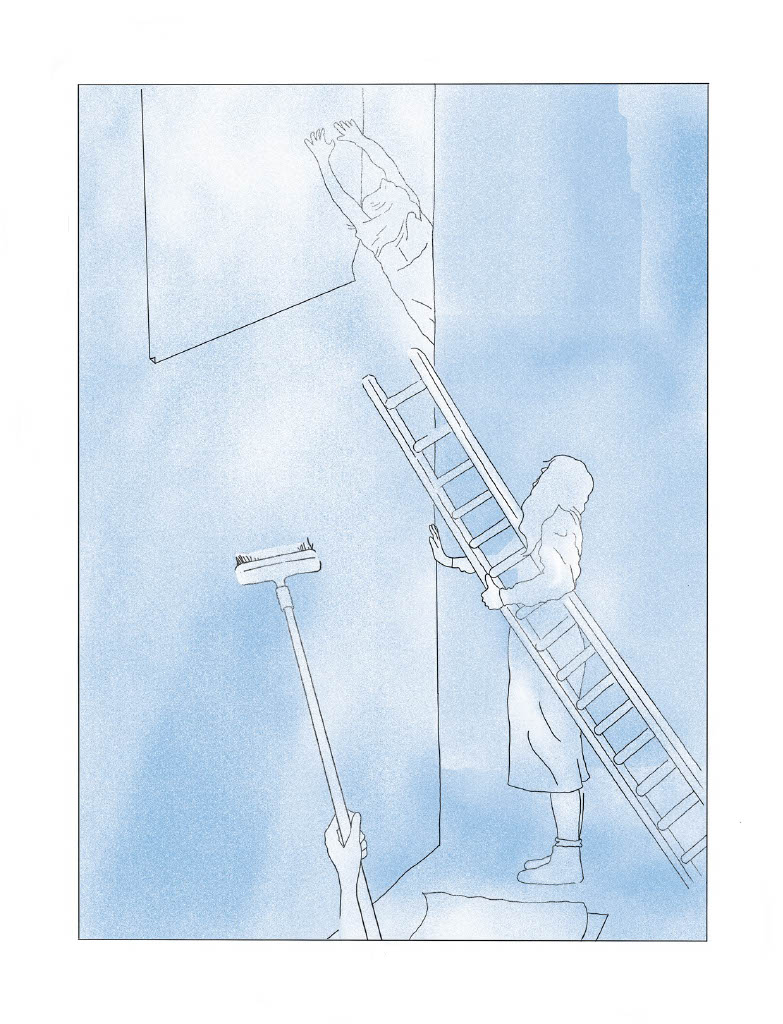

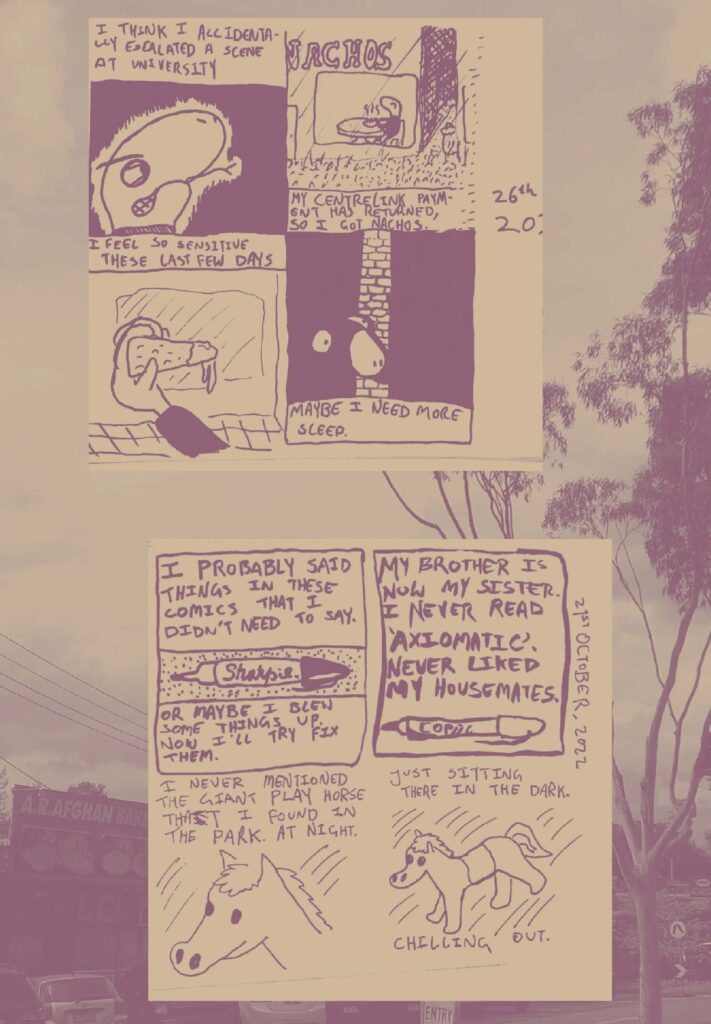

This is an excerpt from Check Points. The full graphic novel can be found here.

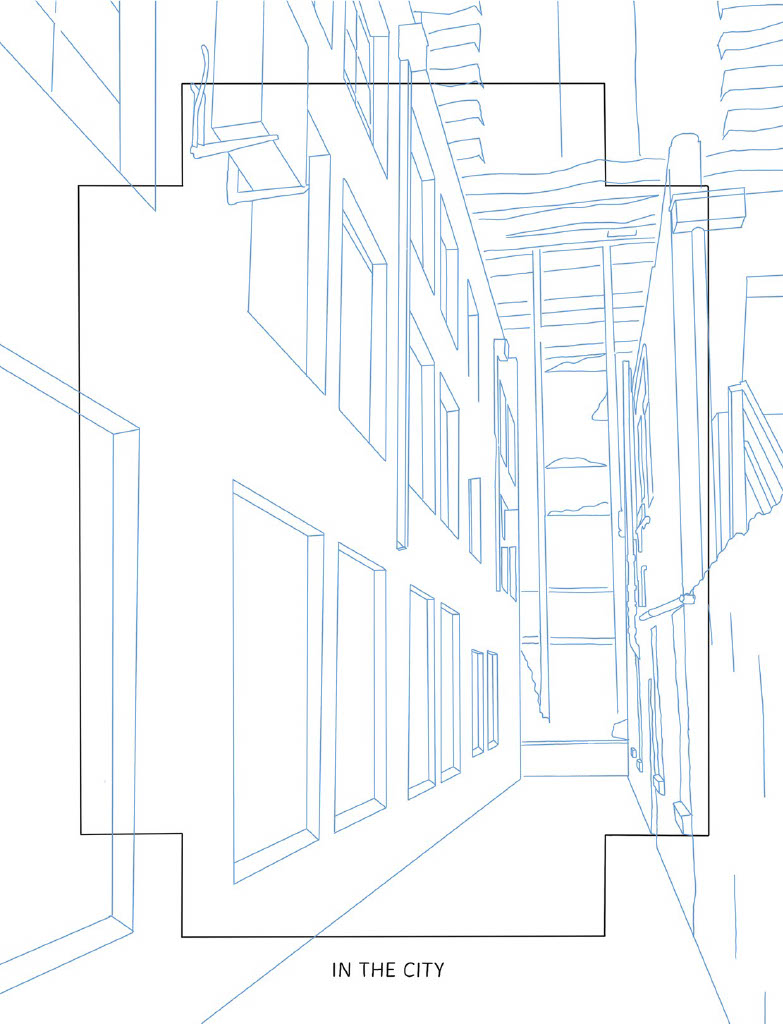

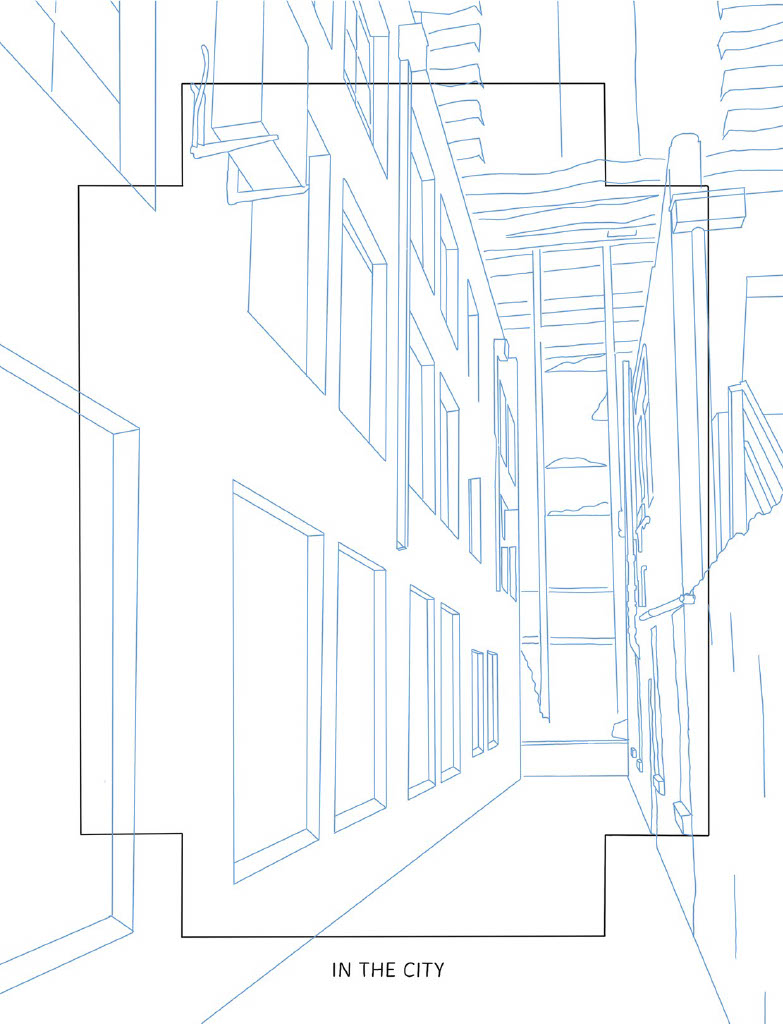

In the city there is no place for those without a reason.

This is an excerpt from Check Points. The full graphic novel can be found here.

It would be a shame to slip away knowing there were visions I hadn’t seen, items I hadn’t possessed. I’m extremely aware of a fact my dad somehow hasn’t learned: life is there to be lived.

My dad has fled to a cottage in the Dandenongs with all his books about the Second World War. My mum is distraught and concerned for his safety, yet furious this has happened once again. I pour her a glass of water and assure her everything will be okay, as long as dad has left behind details on the level of experience I will require in order to successfully reach him. With a deep breath, she hands me a scrap of paper on which my dad has done just that, inviting me to overcome the obstacles and challenges he has left in his wake. These are the kinds of responsibilities that come with being an only child.

I walk next door and ask my neighbour, Renegade Watson, to accompany me. He chomps down hard on a cigar and asks for my assistance with a family matter in return. I agree that once my dad is safely at home, I will help Renegade infiltrate the Australian War Memorial, where his own dad has barricaded himself in order to pay the maximum possible respect. He snarls his approval and slides on a pair of bright blue sunglasses with yellow lenses. I admire him a great deal.

Renegade and I climb into his burnt orange Ford Focus, which he reverses out of his driveway and steers onto the main road. I anticipate a number of rogues may attempt to disrupt our operation, and sit in the passenger seat ensuring my small collection of potions, elixirs and short-range weapons are functional and ready. Renegade switches the radio to his theme tune, which is incredibly catchy while also feeling somewhat timeless. He often plays it when he arrives at a location, or when he leaves one, or when something significant occurs vis-à-vis his emotional state.

‘Feel free to bounce any ideas or questions off me,’ Renegade says, his gaze locked on the road ahead. His companionship and guidance are always invaluable.

‘I will,’ I say. ‘First: where are we going?’

He glances at my dad’s note, which Renegade has taped neatly to the dashboard. ‘If we want to be ready, we need to pay a visit to The Author,’ he says.

‘Who’s The Author?’

Renegade clears his throat. ‘The Author writes tomes that act as Gateways or Portals for dads dedicated to the pursuit of Knowledge. He wears a colourful Bandanna and commands great power. I once penetrated his Victorian Fortress by riding in on an enormous Eagle, but the Eagle and I long ago parted ways. If you’d like to know more about The Author I can add an entry to your Log, which you can access at any time provided we’re not engaged in combat.’

‘Please do,’ I say.

Renegade waves his left hand in the air. My Log beeps. Once all this is over I will review these details to see whether there are any collectibles associated with The Author I should seek out to ensure I hundred percent my life. It would be a shame to slip away knowing there were visions I hadn’t seen, items I hadn’t possessed. I’m extremely aware of a fact my dad somehow hasn’t learned: life is there to be lived.

‘How will we get into the Fortress without an Eagle?’ I ask.

‘This time The Author will invite us in,’ Renegade says. ‘He has a new Task which should allow you to acquire the Knowledge and Experience required to recover your dad.’

It’s beautiful how these things work out, one step following the other.

*

The Author’s fortress is located in East Camberwell, down the road from a large IGA. The nearby buildings are all twisted and warped, teetering towards a gigantic hole. The hole periodically emits bursts of golden coins which shoot into the sky then rain down, a most dangerous fortune. I snap a quick photo of the scene and save it to my Log, along with a reminder to return with a helmet and a sturdy bucket. In the aftermath of a subsequent burst a single coin embeds itself in the arm of a pedestrian, who cries out in pain—or maybe with the joy of discovery.

Renegade rolls his Focus to a stop outside the fortress gates, which are green and gold in colour. They clash in a terrible fashion with Renegade’s car, but there’s nothing I can do about that. We proceed through the gates on foot, past a number of armed guards with no peripheral vision. Though they become alarmed whenever we pass in front of them, they calm down after Renegade shows them the message on a scroll he pulls from the back pocket of his jeans. Sometimes I wish I had his charisma, but never seem to find the time to spend on that particular skillset.

When we enter The Author’s office he is alone, sitting behind a mahogany desk decorated with tiny design concepts for Australian flags. Each features the Southern Cross, but in a different way to the current design, which feels important. A series of landscape paintings line the wall behind him, and I wonder which he enjoys jumping into the most— which holds the greatest adventures.

‘Renegade, you son of a bitch,’ The Author says, smacking a palm on his desk.

Renegade doesn’t waste any time. ‘We’re looking for a dad,’ he growls. ‘His dad. He’s in the Dandenongs. Reading about World War II.’

The Author turns to me. ‘Military history? Social? Cultural? Economic?’ he asks. ‘What are we discussing here?’

‘Military, mainly,’ I say. ‘Some Economic. He’s interested in interrogations of Total War. Strategy. Logistics. Great Man Theory. Fronts, tactics, and such.’

‘A man after my own Heart,’ The Author says. He unwraps his bandanna to reveal a system of cogs protruding from his skull. ‘I had my Brain replaced with this Machine,’ he says, impressively intuiting that I require an explanation. ‘The better you Understand something, the better you can Control it.’

‘You sought control of your own Brain?’

‘It’s a wily one,’ he grins.

‘But we’re talking about the nature of Global War, state-based conflict,’ I say. ‘Control seems out of the question. Even more so than a single human Mind—no offence.’

‘Exactly,’ The Author says. ‘So your Father’s need is Immense.’

Renegade nods gravely.

‘Now, I can help you,’ The Author says. ‘But first, I need your help identifying a Campaign about which I can craft a Book. Then I can allocate you appropriate Equipment from my Armoury, which is sure to help you on your Journey.’

Given their shared interests, I take a moment to recall the cover of every book my dad has ever read. A pattern forms, creativity unleashed within my skull.

‘What if you were to name an already existing but under-examined moment?’ I say. ‘You know, with some kind of Noun.’

‘A Noun,’ The Author repeats.

‘The kid’s right,’ Renegade says. ‘You need to start with a Noun.’

‘Maybe even an Adjective,’ I say.

The Author considers this, then rises from his chair. ‘Brilliant,’ he says. ‘I’ll find a Campaign without a Moniker, and invent it. I’ve always approached these things the other way around.’

He jams a pen between his cogs and powers down, his jaw dropping to reveal a medieval key resting on his tongue. A new door appears to our right, its outline gleaming in the brick wall. Renegade and I enter the armoury and take everything we can carry.

*

Back on the road, Renegade asks if I feel the need to review anything we’ve just experienced.

‘No,’ I say. ‘I was there. But I might try to Remember it later.’

‘Got it,’ he says, then guns the engine.

I can’t help feeling pleased at our progress, though the fact our journey has gone so smoothly makes me suspect danger is imminent. My dad won’t give up researching World War II without a fight. Even if he does, there are other subjects he may move on to at any time, or higher levels of intensity he might seek. I shudder at the prospect of him returning to his fixation on the American Civil War, which has absorbed far too many white Australian dads who share his general demeanor.

‘My old man told me he’d hold a Dawn Service every day if he could,’ Renegade says, like he can read my mind, which I believe he can.

‘I suppose it helps them,’ I say. ‘So they don’t make any big mistakes, like dads throughout history. If they were, you know, to end up in those kinds of positions.’

Renegade says nothing. He just sets his sight on the horizon, the passing landscape reflected in his frames, the scar on his cheek a map to absolution.

This is no metaphor: I realise his scar is in the shape of our region, each outermost point marking a place with opportunities to boost my abilities through small acts of service. When I tell Renegade this he is delighted, and whoops and flexes his biceps to signal his approval. The more we are prepared the less fearful we will be of any of my dad’s plots to keep us at bay.

We drive to Doncaster, where I use my new gear to assist a bottle shop owner to recover their confidence in their singing voice. They direct me back to Camberwell, where I help a busker at the market find their lost hat. The busker advises me to collect a golden orb from the spire of the Arts Centre, which speaks to me in a telekinetic fashion to provide detailed instructions on how to get a frog choir back together again. The frog choristers gift me a fishing rod, which I use to save a baby which is floating along the Yarra in a small wicker basket. I hold it in my arms and bear witness to its glorious smile.

‘It’s okay, baby,’ I say. ‘You’re not a baby any more.’

The baby, who by the time I finish my sentence is a teenage boy and has a bit of an attitude, mumbles a quick thank you, worms his way out of my arms, equips a skateboard and rides off down St Kilda Road. The dust cloud kicked up in his wake reveals a code, which I swiftly crack to determine the address of the cottage in which my dad has hidden away.

*

Renegade and I change into our combat fatigues in the bathroom at a BP, then jump in the car and hurtle towards my dad and his dangerous obsession. So far our quest has been wholesome, filled with connection and interesting imagery. I look forward to having friends I can share the story with, but I know there is more to overcome.

As we merge onto the M3, an old Holden ute speeds up and keeps to our left-hand side. The driver is in his seventies, wisps of grey hair blowing in the breeze, and he wears thick glasses with clear plastic frames all around. As his ute draws level, he uses one hand to throw assorted spikes ahead of our wheels. Renegade swerves to avoid them, spinning out in front of the ute.

‘Did you equip your road set?’ Renegade says, gripping the steering wheel with one hand while he attempts to read out the words of a spell scrawled on a post-it note he holds in the other.

‘Yes,’ I say.

Renegade slams the brakes and our tyres skid until my passenger-side window faces the front of the oncoming ute. I toss a powerful magnet to the asphalt to stop the ute in its tracks before we throttle away. The old man rages in our rear-view mirror, and the message from my dad is clear: I hate my historical reading being disrupted to the same degree as I am passionate about Holden utes.

Renegade and I sit in silence, snaking along the road to our desired location, wind lashing at the car and our thoughts, until—finally—we arrive.

*

Through binoculars I can see the cottage in which my dad has taken refuge. It rests at the top of a hill, surrounded by thick trees on all sides. He’s clearly selected a strategically defensible location. For a moment I feel pride, but soon enough this pride is tinged with resentment. I’ve learned the intrusion of resentment is always a risk, if and when you allow yourself to feel.

Renegade pulls a bush costume from the boot of his car, puts it on over his heavy gear and begins to crawl up the hill, blending into the greenery. I equip a blowdart which causes its victims to have visions of their greatest mistakes. Making my way through trees, passing by my dad’s hired guards, I send darts shooting into the necks of these grown men. The air fills with the sounds of weeping, of cries about past failures and regrets. All I can think is that these men are sons, maybe even dads, and my heart aches as I hear their tales of surround sound systems not connecting to Bluetooth and of family members who enjoyed sport more or less than they did.

I rise over the crest of the hill, the ground behind me littered with forgotten bodies. I make a series of hand signals indicating that Renegade should go around back to create distracting animal sounds, then I crouch by the front door and put my ear to the wood. From inside I can hear a podcast playing. The hosts are discussing whether the Battle of Midway would have ended differently had the Allies’ aggregate economic output been two per cent lower in 1941. My dad is shouting obscenities and pacing about, his footsteps heavy with frustration. Pages rustle as he rummages through his books for the appropriate details to help him rebut their claims, purely for himself. I smile. He hasn’t finished; it’s not too late.

The door is locked, so I use an endless wire controlled by my thoughts to pick it open and tumble through. My dad’s dull eyes follow me as I collapse onto the floor, heavy with the weight of my broadsword and behaviour-altering potions and an AR15 and photographs of people and places I can no longer name. Torn pages are strewn on the floor all around him, and still he mutters.

‘I can solve this,’ he says, while I unspool a thick rope and attach one end to a doorknob.

‘Solve what?’ I say, looping rope under dad’s arms.

‘The War,’ he says. ‘I can understand it, fully and completely. The chain of Causality, the Decisions that were made, every possible Counterfactual at every point in time.’

‘And then what?’ I say, pulling the rope from the other end until he dangles upside down from the ceiling.

Swinging side to side, his head bumping lightly against a shelf, he says, ‘No more questions will remain. Then I’ll understand the next thing, and the thing after that, and after that, and soon I’ll understand it All.’

Before I can respond my ears ring, the result of a large explosion outside. Through the window I see Renegade charging towards the cottage, still wearing a bush, pursued by hundreds of armoured guards equipped with rocket launchers and dogs that bark poison. My dad smiles.

‘It’s over,’ he says.

‘Nothing’s ever over,’ I say. ‘Surely you’ve learned that.’

I pull out one of my elixirs and down it. Time slows to a crawl as I kick the front door open and Renegade and I run from guard to guard, tying their shoelaces together, before returning to the cottage. When my elixir wears off and the guards all fall over at the same moment, yelping in confusion, my dad’s smile disappears.

He swings to a stop until he hangs still, aware he has been bested by the one person he brought into this earth.

‘All this could have been yours,’ he says, waving his arms about to gesture at the thick stacks of hardback books.

‘Not interested,’ I say.

‘You have a good kid,’ Renegade says. ‘You should join him in the real world sometime.’ This is a nice thing to hear.

With Renegade’s help I restrain my seething dad, carry him down the hill and strap him to the roof of the car. I wish I could feel the journey had been a valuable lesson, for me or my dad, but I know this will happen again. It is the way of a certain type of dad, a cultural force beyond my control. Still, it has been nice to escape the drudgery of daily life, even for an afternoon.

As Renegade and I race back along the freeway we laugh and joke, guided by a fresh scar on his left forearm, a gleaming beacon in a world full of darkness and confusion, a safe point in a universe that will never itself be safe.

Debris Mag, 03 The Urge to Know can be found here.

She was startled when the door burst open, pushed by a firm hand then flung inwards by the wind, and a splatter of thick raindrops blew in from the street. They were followed by the most beautiful woman Charlotte had ever seen.

After lunch on Saturdays, the stationery shop owned by George Ross became a quiet refuge from the noise and bustle of Elizabeth Street outside. On Monday mornings it was filled with bankers’ boys and under-clerks buying ledgers and ink for the new week but, as the weekend neared, the flow of customers thinned until Ross and his daughter Charlotte were alone for minutes and even hours at a time. Ross, always frugal, sent the shop boy away at noon and handled the remaining transactions himself.

Occasionally Charlotte would add a purchase to a customer’s account, but largely her days were filled with dusting and tidying and bringing cups of tea, hot and sweet as her father preferred it, to his cluttered desk. In summer, keeping the shop clean could be a continuous activity. The north winds would whip up dust eddies of clay and dried dung in the street outside, which would creep under the door or billow in whenever it blew ajar. The heat was stifling; Charlotte’s broom handle would become slick with sweat and her pen would slide between her damp fingers as she guided it across the page.

But even on the hottest, dirtiest days, Charlotte loved her father’s shop. Its walls were lined with shelves that housed fat leather ledgers, reams of thick, creamy paper and a small selection of three-volume novels brought by boat from England. Beneath the polished wood of the counter tops were cupboards devoted to pens and inks and graphite pencils, and to slim eyedroppers that could fill even the most delicate glass reservoirs. In the front windows, her father displayed a collection of ornate and antiquated ink pots, the number of which rose steadily as friends and associates donated specimens from their own homes. It was his only indulgence; aside, perhaps, from his quiet love for his daughter.

The pair lived above the shop in a suite of rooms that trapped the heat in the summer and seemed to amplify all the din of the street at night. They were neatly kept, however, and well furnished to Charlotte’s simple tastes. Her mother had died of fever following a stillbirth when Charlotte was barely five years old; since then Charlotte had kept house, and her father. She fussed over him when he was so deep in his ledgers that he forgot to eat, reminded him to go to bed if he was distracted by his reading, and ensured his clothing was clean and unmarked by ink—at least at the beginning of the day. As a child, she had hated leaving home for her lessons, fearing that he too would take ill and abandon her if she let him out of her sight for too long. She envied girls who were taught by a governess at home, where they could always keep an eye on their parents. Instead, the Rosses’ maid took her in a cab to her first school in Carlton, and later to the ladies’ college in East Melbourne.

Mrs Bunton was more to the Rosses than her title suggested, and to Charlotte in particular once her mother was gone. She cooked their meals and did the heavy housework, but she also comforted Charlotte if she fell and scraped her knees or stood in as chaperone when George Ross was busy. As Charlotte grew older and more capable, less was asked of Mrs Bunton, but she continued to cook and clean for them, leaving Charlotte to spend most of her time downstairs. She served customers sometimes, but more often she copied invoices for her father in her neat, womanly hand. She memorised the wording as she did so, and as she filed the paperwork in the

drawers at the back of the shop, she scrutinised the carbons carefully, learning about shipping times and order quantities and mark-ups, and the polite way to tell a supplier that his prices were too high. When the shop was quiet, she would run her fingers over the curves of thick leather spines and daydream about owning her own shop, which, in her mind, was this one, filled with ink and paper and words—and a sense of purpose.

She knew better than to speak of such dreams to her father. He clung to the belief that Charlotte would be happiest well married and mother to a flock of red-cheeked boys. A man in trade or a fellow shopkeeper, he thought: steady and without pretension. When Charlotte imagined this she felt her stomach lurch and her breath come thin and fast, and she concentrated on entering long lines of numbers into the accounts ledger until the sums came out right and her father’s vision for her future receded.

Charlotte had few friends, but she was not lonely. She loved her father and their quiet life and the calm routine of her existence. She had no reason to wonder what she might be lacking until the day Flora Dalton swept through the stationery shop’s broad wooden door.

The new year had arrived days earlier, bringing with it a heavy, sticky heat that left Charlotte feeling weary and short of breath. The promised rain had begun, finally, that morning and had quickly turned the streets into quagmires of mud and horse muck, scored by rivulets of clay-yellow water rushing downhill, as Elizabeth Street reached back in time to become the creek it had once been. Charlotte had just washed the shop windows, but now their lower halves were spattered with the same grime as the flooring near the shop door.

The terrible weather meant that there were fewer customers than usual, so Charlotte chose a novel from the shop’s stocks to read between her trips upstairs for her father’s tea, and quickly became lost in the story.

She was startled when the door burst open, pushed by a firm hand then flung inwards by the wind, and a splatter of thick raindrops blew in from the street. They were followed by the most beautiful woman Charlotte had ever seen. Her fair hair hung in damp curls and her silk skirts were soaked through at the floor and clinging to her feet, but such minor imperfections seemed only to render her warm brown eyes and bright complexion more arresting. It was not only her beauty, however, that froze Charlotte in her place. The air in the shop seemed to spark with new energy: to be enlivened by the woman’s very presence. Her shoulders were straight and her expression open—she was as comfortable here as she would be in her own home. This was a woman, Charlotte thought instantly, who was unaccustomed to self-doubt.

She might well have remained mute and staring if her father’s soft cough hadn’t brought her to her senses.

‘Oh dear. I’m sorry,’ she said, hurriedly marking her place in the book with an old invoice. She placed the book carefully on the counter and moved forward to greet their customer. ‘May I assist you with anything?’

The woman favoured her with an easy smile that induced an odd, tight feeling deep in Charlotte’s chest. ‘What a charming shop you have!’ she said. Her voice, as predicted by her appearance, was beautiful. Light and melodic, with an underlying note of laughter. ‘Why, if Jimmy had told me, I’d have come here sooner.’

‘Jimmy?’ Charlotte’s tongue felt thick and clumsy in her mouth.

‘My brother,’ the woman said, as though it should be obvious. ‘Father sends him to fetch the orders, and he speaks of it as though it were a great trial instead of a pleasant walk with a pretty little shop at the end of it.’

Charlotte’s eyes darted towards the mud-strewn windows, before being drawn back to the woman’s softly rounded face.

‘Well, it would be pleasant on a day more suited to it,’ she went on, looking around the shop and taking in the dark wood fittings and the counters: glass-topped, to display neat lines of pens, nibs and inkpots, some unremarkable and some ornate. ‘Today it was rather more an adventure. At one point I thought my cab might float away.’

‘It’s a good thing it didn’t,’ Charlotte said. ‘Half the men in Melbourne would’ve taken it upon themselves to rescue you—and not one of them up to the task. You’d have been expected to sit there and drown if it came to it. Never mind whether you knew how to swim.’

The woman’s roaming gaze snapped back to Charlotte’s face and she studied her with a new intensity. Not accustomed to much more than a cursory glance from the shop’s customers, Charlotte felt oddly vulnerable, as though the woman wasn’t looking at her so much as through her. She had to fight the urge to look down.

‘You sound like you’re speaking from experience,’ the woman said, brows raised, the corners of her lips betraying the hint of a smile.

Only then did Charlotte realise how inappropriately blunt she’d been. This stranger would undoubtedly see gallantry in the forceful protectiveness of gentlemen. ‘I have a good imagination,’ she said, cheeks burning, ‘and a bad habit of speaking without thinking. I apologise. How can I help you?’

The woman waved the question away with a graceful flick of the hand. ‘You should never apologise for being interesting,’ she said. ‘Very few people are, I find. Least of all those who lay claim to it.’

Still Charlotte berated herself for speaking so rudely. She always felt awkward in conversation: talking either too much or not enough. But this woman made her feel particularly gauche, as though simply being near her had stripped every intelligent thought from Charlotte’s mind. Her gaze fell desperately on the window and the rain beating against it.

‘Your father must need stationery quite urgently,’ she said, feeling stupid.

The woman smiled—a true smile this time—and adjusted smoothly to the change of subject. ‘More that I was in dire need of an escape,’ she said. ‘My brother has a headache, poor dear, which means that we must all suffer alongside him. A little rain seemed quite tolerable in comparison.’ The chatter ran on, effortlessly engaging, until her focus sharpened on Charlotte once more. ‘But I’m forgetting myself,’ she said. ‘You must think me terribly barbaric. I’m Flora Dalton, and I’m very pleased to make your acquaintance.’

She offered her hand, and there was something in the way she looked at Charlotte that made the words sound genuine. Kind, Charlotte thought, as well as beautiful. She must be aware of Charlotte’s embarrassment, but she acted as though there was no cause for it. Her eyes were wide and intelligent, and they regarded Charlotte with curiosity, not disdain.

‘Charlotte Ross,’ she said, and when she took Flora’s hand, just a brief meeting of fingers, something sparked within her: an unfamiliar heat. Flora frowned—a slight flickering of the brows that would have been invisible had Charlotte’s gaze not been so fixed upon her face—and dropped her hand with a brief laugh that did not reach her eyes.

House of Longing can be found here.

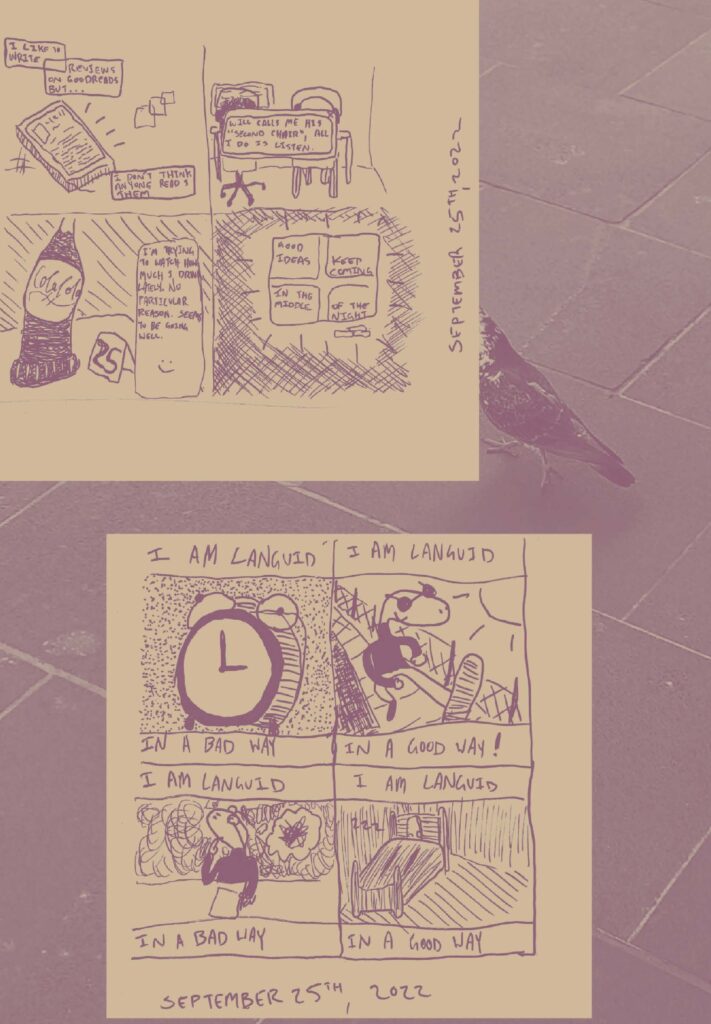

I am languid in a bad way

I am languid in a good way!

Verrition: an untranslatable term Césaire used to indicate a kind of sweeping. Not really: it was a term to indicate the double jouissance of licking words, over and over again.

1.

Verrition: an untranslatable term Césaire used to indicate a kind of sweeping. Not really: it was a term to indicate the double jouissance of licking words, over and over again. But that is not unlike sweeping, and sweeping is not unlike action painting, your heft and back pushing bristles as they sound off, marking the floor with a tacky rub, or licking the ground, over and over again.

Maybe we could buy a new broom at Bunnings? That question hovers for minutes, days. Maybe we could find ourselves licking the ground at the interval between days, between minutes, between the 59 and the 0? What is the interval between days, between night and day? (Le petit matin, Césaire called it, which Walcott translated, and I find plausible, as foreday morning.) Cognitive drowning, or a tortured landscape in foreday morning, then. Drowning before or at the fore of the zero, which is day. What I mean is that this is not the only thing tethered to the fore of a zero thing, the foreday thing, which is not only an aesthetic thing. And the inclusion of human references here will not be decorative. Except the conclusion here might be decorative, assuming the human will have already existed.

I can’t open it, I say, when I can’t open a file or a link, when I don’t have the password anymore. I can’t open it anymore. But then I thought I was in a landscape or countryside. The file or the link was in the countryside. How do I open a link out there? What if I don’t know the password? What if I don’t know the countryside—which countryside—the institutional countryside—that has disordered my relationship with passwords? My body seizing, pushing bristles as they sound off. This would be me, from the countryside.

Glissant says, I am less interested in your origins in the countryside than in how you would draw a tree, for instance, which is no longer genealogical nor biographical when the picture includes the soil, the manure, the grasses, the birds, the water in the air, the water in the ground, the water on the leaves, the adjacent trees, all the condensation from all the leaves, the clouds humming in the blue hinterland. Humming is historical. Is it biographical, but no longer intimate? Or is it intimate, but no longer personal; that is, no longer a person? Waiting for a live one in a tortured landscape: humming. This is not Glissant talking anymore, this is someone else. This would be me. The notion of privacy is an intensely held public notion; quite the sacred notion, if a notion can be spoken about as sacred. This morning me and my notion tentatively called the Magistrate’s Court, passing through a number of institutional countrysides into the sacred countryside where the private matter could be dealt with. Then, more boldly, we called the Carpet Court. We ordered 59 kilometres squared of carpet. We wanted to lay it down and lick the ground, over and over again.

2

At some point I try to tally roughly how many times I texted ‘Leo is leaving this Monday’ or ‘Leo left this Monday’, usually prefaced with ‘I’m not sure if I already told you, but—’ or suffixed with ‘—I thought you should know’. Three times would have been ideal. I went for a walk at night in Lorne, at some point I thought to do it, as a context. Shape of the bay and shape of the moon, plausibly analogous. A plausible analogy. An old Italian man in my car is at me about poetics, because it takes me a long time to understand things I love. A woman eats a rotisserie chicken. One hand holds the chicken. The other hand, covered in a plastic bag, prises the flesh apart. Her mouth holds something key—the neck?—in place. I wear the new PSG jersey to the little bar they have here and the staff at the bar go absolutely nuts. They go absolutely nuts. Which was probably, somehow, key: the neck of the plan.

Last night on the phone to Cam he told me he was the Ian Thorpe of chillin’ and I said, yep, you’re the chill-pedo and we both laughed and laughed, because my god there were so many levels to it. Like, two levels! And then because I was already getting off the phone I said, how the fuck can you follow chill-pedo, and at the same moment Cam said, who the fuck can I call now?

3

The thing with protest is that it involves a lot of singing. Protest is the thing that involves a lot of singing. I am sitting on the Rathdowne St side of Carlton Gardens, near the corner of Victoria Pde. I have just finished work and I’m wearing my stupid work clothes, which protect me from being mistaken for a member of Extinction Rebellion, who set up camp here only a few hours ago only a few metres away. The XR camp is enclosed by an improvised fence made of washing line from which XR logo-ed tee-shirts hang. When I sit down, a trio of women are singing the Stop Adani song and I’m reminded of the claim I overheard once at a meeting to organise a protest immediately following the detention of DW embassy leader, DT Zellanach. Some guy in a wide-brimmed hat and hiking clothes was rifling through his soft briefcase full of sheet music, explaining to a pondy young woman that he is responsible for a number of the ‘current chants’, and that his authorship extends to ‘Coal, don’t dig it / Leave it in the ground it’s time to get with it’. I don’t know why I don’t believe this easily plausible claim. The same week I attended that meeting about DT Zellanach, a local squatter in the house near the bike track told me he is currently involved in several legal cases, including one with Jay Z for part-songwriting credit for Rihanna’s ‘Umbrella’. He told me this after asking me if I worked for the local council, thinking he was about to tell me to get fucked, concerned about the meaning of my work clothes. That claim about ‘Umbrella’ is a claim I am willing to entertain because it’s more entertaining and therefore more plausible.

A few police shift about in the park, looking embarrassed, perhaps by XR’s singing or perhaps by their own patrolling. They are humming, their own singing. I keep going to these things, though I keep reverting to this abstract journalism. Patrolling the singing, oh, the bloody singing: this is a wild desire to leave. Though we believe it when the protestors say this is an emergency.

There is a ‘smoking area’ that XR has set up near a river red gum outside the tee-shirt fence. On the back of a placard, the painted words say: ‘Smoking Area: Bin Your Butts!’ I stare at this sign for a long time. Under the river red gum, a young man and a young woman are slowly, but slowly, kissing. Last time I looked at them, before I began staring at the Bin Your Butts sign, they were simply staring into each other’s eyes, legs crossed. I can’t decide whether it is weird or completely unweird that everyone at the XR camp is white. I can’t decide if it’s weird that I wear a suit to work when there’s no dress code at work and basically no one ever sees me at work and, basically, I’m not even sure I’m really in work.

As I leave for my conventionally parked and recently washed car, I see the XR march coming up Exhibition St, singing the Stop Adani song. People clap on beat. People beat a drum. A police car parallel parks in the space behind me. The song sounds like what I imagine a dirge must sound like. Only now I realise I’ve never knowingly heard a dirge before. The policeman in the car scrapes his left wheels against the kerb. He nearly doors a cyclist. I have a feeling I shouldn’t leave. The feeling is a dirge.

As I drive away, the radio plays an article about how the number of volunteer firefighters has been in decline since Black Saturday, in part due to the trauma of that event, in part because the weather is changing in a way that’s unpredictable, so that no training can prepare someone to do this job. The weather is changing. Verrition, over and over: something so plausible I’m swept away.

CONCLUSION

The water in the kettle is dancing, says Leo. Can I use that, I ask.

Do you guys have any money, I ask. Cash money. Good point, says Mel, walking a $5 note to the man sitting on the ground in our path. Actually, I say, I want to go use the photobooth on the other side of the station. It only takes one- and two-dollar coins. Six bucks for four photos, I say. This is taken as a passing comment, because we never cross the bridge to the photobooth, not heading out west and not coming back east to the car.

We should go to the Skydeck when this is over, I say. The path to the Skydeck crosses our path, reminding me of the time I went to the Skydeck in a fever after speaking at the photography college. I’m afraid of heights, but sure, says Mel. That feeling of heights, explains Leo, is the body recalling a previous experience of falling. You feel it in your groin, I say. Yes, they both say. The past is a feeling in the groin, no one says.

Somewhere after Queensbridge we lose our bearings following the river west. In an alcove under the Bolte Bridge, a department relevant to the river or the bridge has left a notice on a door. Do not venture further, it says. We look at the West Gate Bridge, which is closer than we remember. It’s a destination we don’t make this day, but a few days later those boys will get there. It doesn’t make it to the news, but when they make the middle of the bridge, those boys start dancing.

Reading the City of Literature is a snapshot of Melbourne’s literary activity over the span of a year. It’s been a while since our last Reading the City of Literature, but we are happy to say that it’s back.

So please scroll through this whole website, click, read and share!

In 2008, Melbourne joined the UNESCO Creative Cities Network, when it was designated the first Australian City of Literature, and the second ever City of Literature in the world.

This designation as a UNESCO City of Literature is an acknowledgment of the breadth, depth and vibrancy of the city’s literary culture. We are proud to call Melbourne home to an exciting and broad range of writers, publishers, booksellers, literary organisations, events and festivals.

Reading the City of Literature is a snapshot of Melbourne’s literary activity over the span of a year. It’s been a while since our last Reading the City of Literature, but we are happy to say that it’s back.

So please scroll through this whole website, click, read and share!

About the Melbourne UNESCO City of Literature Office

The Melbourne UNESCO City of Literature Office is responsible for celebrating and promoting this designation and everything literary Melbourne has to offer.

The Office’s role involves supporting the work and networks that exist, nurturing and developing new opportunities and networks, making connections across industry and audiences and championing all things Melbourne as a City of Literature. This is achieved through strategic initiatives, partnership programs and international exchanges.

The Office has three broad areas of action that address the aims of the Creative City Network as well as the needs for Melbourne as a City of Literature: Connecting the City of Literature, Reflecting the City of Literature and Supporting the City of Literature.

The Melbourne UNESCO City of Literature Office is a joint initiative of Creative Victoria and City of Melbourne and is hosted by The Wheeler Centre.

What a tremendous gift it would have been, to have known that there were people in history who might now be called trans, people who lived as the genders they knew that they were, regardless of what society had told them.

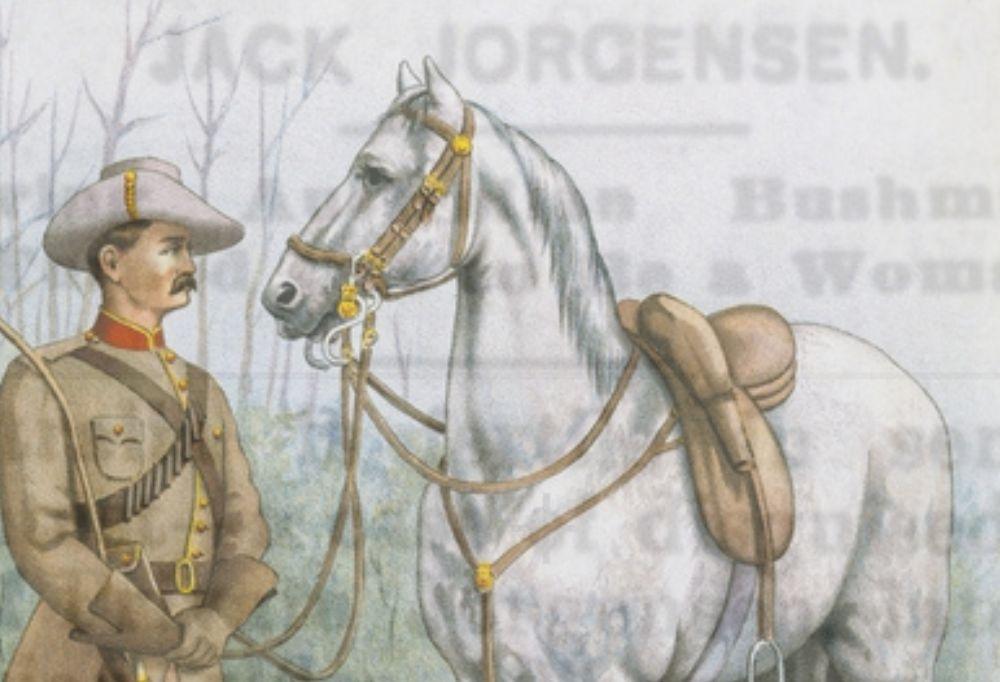

In a moment of growing backlash towards the transgender community, I’ve been drawn to the history books. The story of a Victorian man whose death in 1893 became a sensationalised headline reminds us that gender non-conforming people have always been here.

In 1893, a 42-year-old man died on the floor of a rickety old stockman’s hut in Elmore, a small Victorian town on the lower reaches of the Campaspe River. He’d refused multiple offers to be taken to the nearby hospital in Bendigo and took his last gasping asthmatic breaths huddled in a dusty blanket.

Shortly following his death, a sensational report was published in the Bendigo Independent:

Perhaps the most surprising item of the day’s news is the discovery that a farm labourer at Elmore, member of the mounted rifles who died on Tuesday is discovered to be a woman. Nobody suspected her sex. She took part in the rough work of the farm. She gratified her martial instincts by joining the mounted rifles, be-straddled her steed and learned to gallop and wheel and shoot with the best of her comrades, and no doubt in actual war would have stood fire with the coolest of them. And yet, all the while she was a woman.

—Bendigo Independent, 7 September 1893

The man was called Johann Martin ‘Jack’ Jorgensen. His sister, Mrs Theresa Neumann, who travelled from South Australia to Bendigo to identify the body provided an origin story of sorts. She said that ‘Johanna’, had been ‘a pretty girl until she’d been kicked in the face by a horse’, leaving the teenager with a flattened nose, damaged eye and scarred face. Their family had subsequently emigrated from Germany to Adelaide, where they all lived together until Jorgensen’s parents became ‘much annoyed’ by his insistence on wearing male attire. Instead of falling into line, Jorgensen left his family far behind, bound for the Goldfields of Victoria.

*

One hundred and fifty years later, I too moved to the east coast in search of a more authentic life. While in the early stages of my own gender journey, I was always on the hunt for people like myself in history; I was always searching for proof that I wasn’t crazy, brainwashed or a fad. Jack Jorgensen soon reared his head in Joseph Furphy’s Such is Life, immortalised as ‘Nosey Alf’ in that ubiquitous Australian classic. I found more evidence of my kind in Lucy Chesser’s seminal text, Parting with My Sex: Cross-Dressing, Inversion and Sexuality in Australian Cultural Life. Suddenly, my imagination was filled with gender transgressors who too had called this place their home.

In their 2017 book, Trans Like Me, CN Lester wistfully reflects on this urge to find yourself in the past:

What a tremendous gift it would have been, to have known that there were people in history who might now be called trans, people who lived as the genders they knew that they were, regardless of what society had told them. To know that they had claimed their own lives with honesty and courage, and that maybe I could follow their lead and do the same.

I gobbled up antiquated newspaper articles on Trove, taking in every detail of Jack’s portrayal. One long-dead wordsmith from the 7 September 1893 edition of the Ballarat Courier provided the following sketch:

[Though] she was tall and powerful, and capable of lifting very great weights … [and] her masculine clothes appeared to be worn in a natural manner, there was a feminine tone in her voice which she could not quite conceal.

Apart from the tall and powerful part, I could relate.

In an article that wouldn’t be out of place in a current edition of The Australian, except perhaps for its literary verve, a correspondent from the 8 September 1893 issue of the Bendigo Independent went on to ponder the reason behind Jack’s decision to live his life in a different gender:

Nobody can quite explain the impulse which so continually impels women to undertake a lifelong hypocrisy of the kind described. Is there a subtle quarrel betwixt the sex of the soul and body in these cases, or does the disguise carried out with such amazing resolution and ingenuity, represent mere feminine perversity, the disgust of a woman with their own sex and its conditions? These female imposters in breeches are not on the whole entitled to much admiration. But at least they display a capacity for sustained and obstinate purpose which applied to better ends would deserve unbounded praise.

As I followed the trial of Jack’s life in old newspapers, I looked for my own answers buried within his life story.

*

Once he’d left his family and arrived in the Goldfields, Jack soon found work as a cook at Craven’s Hotel in Heathcote, requiring him to wear his female attire. Before long, he’d returned to wearing breeches and a shirt to take up a role on a farm building fences but was soon arrested for this gender transgression.

I read on eagerly as one Constable Dwyer provided an account of Jack’s own words. ‘After arresting her she said the men’s clothes suited her better than woman’s; that she was always called a man when in female attire and called bad names.’

This too rang a bell.

I was imagining myself in Jack’s place, shocked and humiliated, being tried as a criminal for simply going to work. I was heartened to read his employer John Duff speak up in his favour: ‘I engaged her as a man to work on my land. She was dressed in man’s attire. She worked hard. She was a very good and willing person to work. I know of nothing against her character.’

The Magistrate dismissed the case but ordered Jack to resume wearing dresses. At this, he pleaded to be allowed to remain in male attire, ‘stating that she had always been accustomed to do so as a boy in Germany, she had fought as a man in the army, and … had a better feeling towards the ladies than the gentleman’.

To speak these unspeakable words in a courtroom; I was in awe of his bravery.

The magistrate refused Jack’s request, stating that ‘the laws of the country would not permit her to wear any other than the attire of her own sex.’

But Jack did not acquiesce.

Instead, he moved thirty miles away to the town of Runnymede to continue his life as a man. He bought land, joined a volunteer cavalry corps, and even voted in elections (a privilege denied to settler women until 1902, and to Indigenous people until 1962). Later described by his comrades as ‘a short and stubbly, eccentric fellow’ who spoke in broken English in an unusual, falsetto voice, Jack was well-regarded for his excellent horsemanship, sobriety, and first-rate culinary skills. According to the newspapers, his many efforts to find a wife were unsuccessful, a fact that caused him considerable heartache throughout his life.

*

A question haunted me while scouring over what remains of Jack’s life: Did Jack have to die so young in that dusty bush shack? Why did he refuse to go to hospital? Was the sad case of Edward de Lacy Evans, a fellow Goldfields gender transgressor ringing in his ears? He must’ve surely read it as a cautionary tale.

De Lacy Evans, a thrice-married Goldfield’s quartz miner, was taken to Bendigo Hospital against his will in 1879 following a workplace accident. After refusing to undress and attempting to escape, de Lacy Evans was committed to the Bendigo lunacy ward and sent on to Kew Asylum in Melbourne. There, he was forcibly stripped and was revealed to be biologically female, triggering a cruel and salacious national media scandal.

This news coverage must’ve terrified Jack. Does that explain his apparent decision to choose death over shame, humiliation and being forced to live the rest of his life as a woman?

What must his last moments have been like knowing that his lifeless body would soon betray his secret? Was his past even really a secret to those rough-living men who pleaded with him to go to hospital? Country townsfolk always know each other’s business.

*

It’s a melancholy truth that queer and trans people tend to find evidence of their own kind in the history books when things have gone horribly wrong for them. So, I’m comforted to know that in this tale at least, Jack died on his own terms after living the life he’d chosen for himself.

But while I’m taking comfort in Jack’s legacy, what would he make of me? Could he have imagined that someone like him with access to mind-boggling hormone and surgical treatments would pick over the few words he spoke on the public record in a tiny, rural police court on one of the worst days of his life? Would he be proud of his posthumous visibility?

Or maybe he would shout at me in his falsetto, German-tinged voice, and tell me to stop poring over his bloody private business and to get a real job?