In a moment of growing backlash towards the transgender community, I’ve been drawn to the history books. The story of a Victorian man whose death in 1893 became a sensationalised headline reminds us that gender non-conforming people have always been here.

In 1893, a 42-year-old man died on the floor of a rickety old stockman’s hut in Elmore, a small Victorian town on the lower reaches of the Campaspe River. He’d refused multiple offers to be taken to the nearby hospital in Bendigo and took his last gasping asthmatic breaths huddled in a dusty blanket.

Shortly following his death, a sensational report was published in the Bendigo Independent:

Perhaps the most surprising item of the day’s news is the discovery that a farm labourer at Elmore, member of the mounted rifles who died on Tuesday is discovered to be a woman. Nobody suspected her sex. She took part in the rough work of the farm. She gratified her martial instincts by joining the mounted rifles, be-straddled her steed and learned to gallop and wheel and shoot with the best of her comrades, and no doubt in actual war would have stood fire with the coolest of them. And yet, all the while she was a woman.

—Bendigo Independent, 7 September 1893

The man was called Johann Martin ‘Jack’ Jorgensen. His sister, Mrs Theresa Neumann, who travelled from South Australia to Bendigo to identify the body provided an origin story of sorts. She said that ‘Johanna’, had been ‘a pretty girl until she’d been kicked in the face by a horse’, leaving the teenager with a flattened nose, damaged eye and scarred face. Their family had subsequently emigrated from Germany to Adelaide, where they all lived together until Jorgensen’s parents became ‘much annoyed’ by his insistence on wearing male attire. Instead of falling into line, Jorgensen left his family far behind, bound for the Goldfields of Victoria.

*

One hundred and fifty years later, I too moved to the east coast in search of a more authentic life. While in the early stages of my own gender journey, I was always on the hunt for people like myself in history; I was always searching for proof that I wasn’t crazy, brainwashed or a fad. Jack Jorgensen soon reared his head in Joseph Furphy’s Such is Life, immortalised as ‘Nosey Alf’ in that ubiquitous Australian classic. I found more evidence of my kind in Lucy Chesser’s seminal text, Parting with My Sex: Cross-Dressing, Inversion and Sexuality in Australian Cultural Life. Suddenly, my imagination was filled with gender transgressors who too had called this place their home.

In their 2017 book, Trans Like Me, CN Lester wistfully reflects on this urge to find yourself in the past:

What a tremendous gift it would have been, to have known that there were people in history who might now be called trans, people who lived as the genders they knew that they were, regardless of what society had told them. To know that they had claimed their own lives with honesty and courage, and that maybe I could follow their lead and do the same.

I gobbled up antiquated newspaper articles on Trove, taking in every detail of Jack’s portrayal. One long-dead wordsmith from the 7 September 1893 edition of the Ballarat Courier provided the following sketch:

[Though] she was tall and powerful, and capable of lifting very great weights … [and] her masculine clothes appeared to be worn in a natural manner, there was a feminine tone in her voice which she could not quite conceal.

Apart from the tall and powerful part, I could relate.

In an article that wouldn’t be out of place in a current edition of The Australian, except perhaps for its literary verve, a correspondent from the 8 September 1893 issue of the Bendigo Independent went on to ponder the reason behind Jack’s decision to live his life in a different gender:

Nobody can quite explain the impulse which so continually impels women to undertake a lifelong hypocrisy of the kind described. Is there a subtle quarrel betwixt the sex of the soul and body in these cases, or does the disguise carried out with such amazing resolution and ingenuity, represent mere feminine perversity, the disgust of a woman with their own sex and its conditions? These female imposters in breeches are not on the whole entitled to much admiration. But at least they display a capacity for sustained and obstinate purpose which applied to better ends would deserve unbounded praise.

As I followed the trial of Jack’s life in old newspapers, I looked for my own answers buried within his life story.

*

Once he’d left his family and arrived in the Goldfields, Jack soon found work as a cook at Craven’s Hotel in Heathcote, requiring him to wear his female attire. Before long, he’d returned to wearing breeches and a shirt to take up a role on a farm building fences but was soon arrested for this gender transgression.

I read on eagerly as one Constable Dwyer provided an account of Jack’s own words. ‘After arresting her she said the men’s clothes suited her better than woman’s; that she was always called a man when in female attire and called bad names.’

This too rang a bell.

I was imagining myself in Jack’s place, shocked and humiliated, being tried as a criminal for simply going to work. I was heartened to read his employer John Duff speak up in his favour: ‘I engaged her as a man to work on my land. She was dressed in man’s attire. She worked hard. She was a very good and willing person to work. I know of nothing against her character.’

The Magistrate dismissed the case but ordered Jack to resume wearing dresses. At this, he pleaded to be allowed to remain in male attire, ‘stating that she had always been accustomed to do so as a boy in Germany, she had fought as a man in the army, and … had a better feeling towards the ladies than the gentleman’.

To speak these unspeakable words in a courtroom; I was in awe of his bravery.

The magistrate refused Jack’s request, stating that ‘the laws of the country would not permit her to wear any other than the attire of her own sex.’

But Jack did not acquiesce.

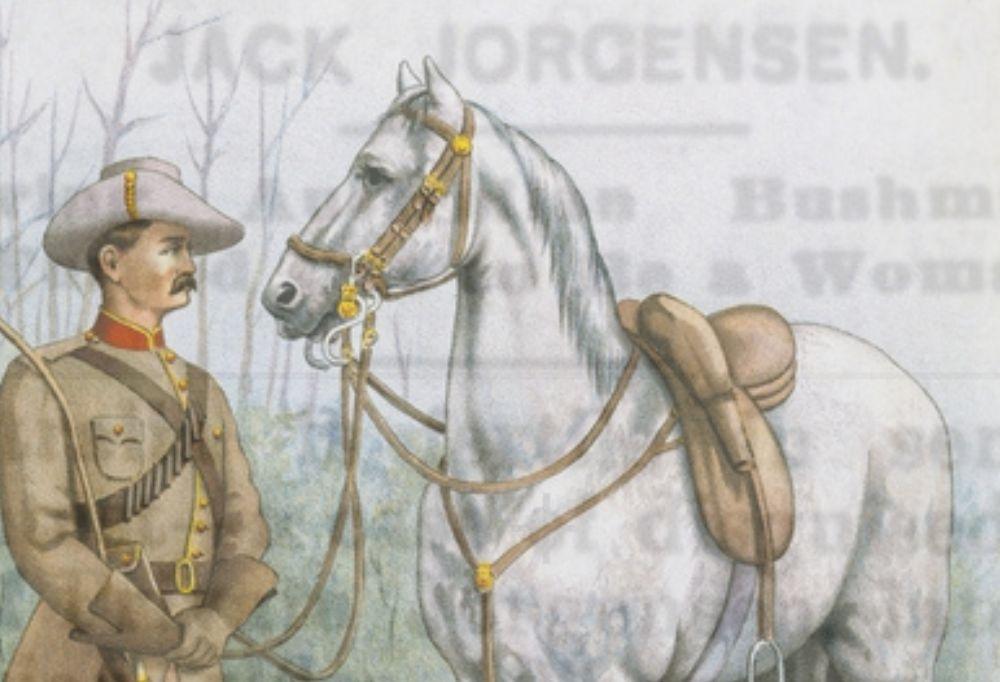

Instead, he moved thirty miles away to the town of Runnymede to continue his life as a man. He bought land, joined a volunteer cavalry corps, and even voted in elections (a privilege denied to settler women until 1902, and to Indigenous people until 1962). Later described by his comrades as ‘a short and stubbly, eccentric fellow’ who spoke in broken English in an unusual, falsetto voice, Jack was well-regarded for his excellent horsemanship, sobriety, and first-rate culinary skills. According to the newspapers, his many efforts to find a wife were unsuccessful, a fact that caused him considerable heartache throughout his life.

*

A question haunted me while scouring over what remains of Jack’s life: Did Jack have to die so young in that dusty bush shack? Why did he refuse to go to hospital? Was the sad case of Edward de Lacy Evans, a fellow Goldfields gender transgressor ringing in his ears? He must’ve surely read it as a cautionary tale.

De Lacy Evans, a thrice-married Goldfield’s quartz miner, was taken to Bendigo Hospital against his will in 1879 following a workplace accident. After refusing to undress and attempting to escape, de Lacy Evans was committed to the Bendigo lunacy ward and sent on to Kew Asylum in Melbourne. There, he was forcibly stripped and was revealed to be biologically female, triggering a cruel and salacious national media scandal.

This news coverage must’ve terrified Jack. Does that explain his apparent decision to choose death over shame, humiliation and being forced to live the rest of his life as a woman?

What must his last moments have been like knowing that his lifeless body would soon betray his secret? Was his past even really a secret to those rough-living men who pleaded with him to go to hospital? Country townsfolk always know each other’s business.

*

It’s a melancholy truth that queer and trans people tend to find evidence of their own kind in the history books when things have gone horribly wrong for them. So, I’m comforted to know that in this tale at least, Jack died on his own terms after living the life he’d chosen for himself.

But while I’m taking comfort in Jack’s legacy, what would he make of me? Could he have imagined that someone like him with access to mind-boggling hormone and surgical treatments would pick over the few words he spoke on the public record in a tiny, rural police court on one of the worst days of his life? Would he be proud of his posthumous visibility?

Or maybe he would shout at me in his falsetto, German-tinged voice, and tell me to stop poring over his bloody private business and to get a real job?